Las Vegas

— I can't shake the feeling that I'm going to die again, soon.

Somehow they keep building buildings. They tear the old ones down. Put new ones up. Divide them up into rooms, people come, people go. I can't imagine many stay very long. My soul tired. How do I stop you from entering this place?

Already, a lapse, a failure. It becomes part of the structure — it can be buffed out, erased, replaced. The center cannot hold. Fears of another end of the world loom.

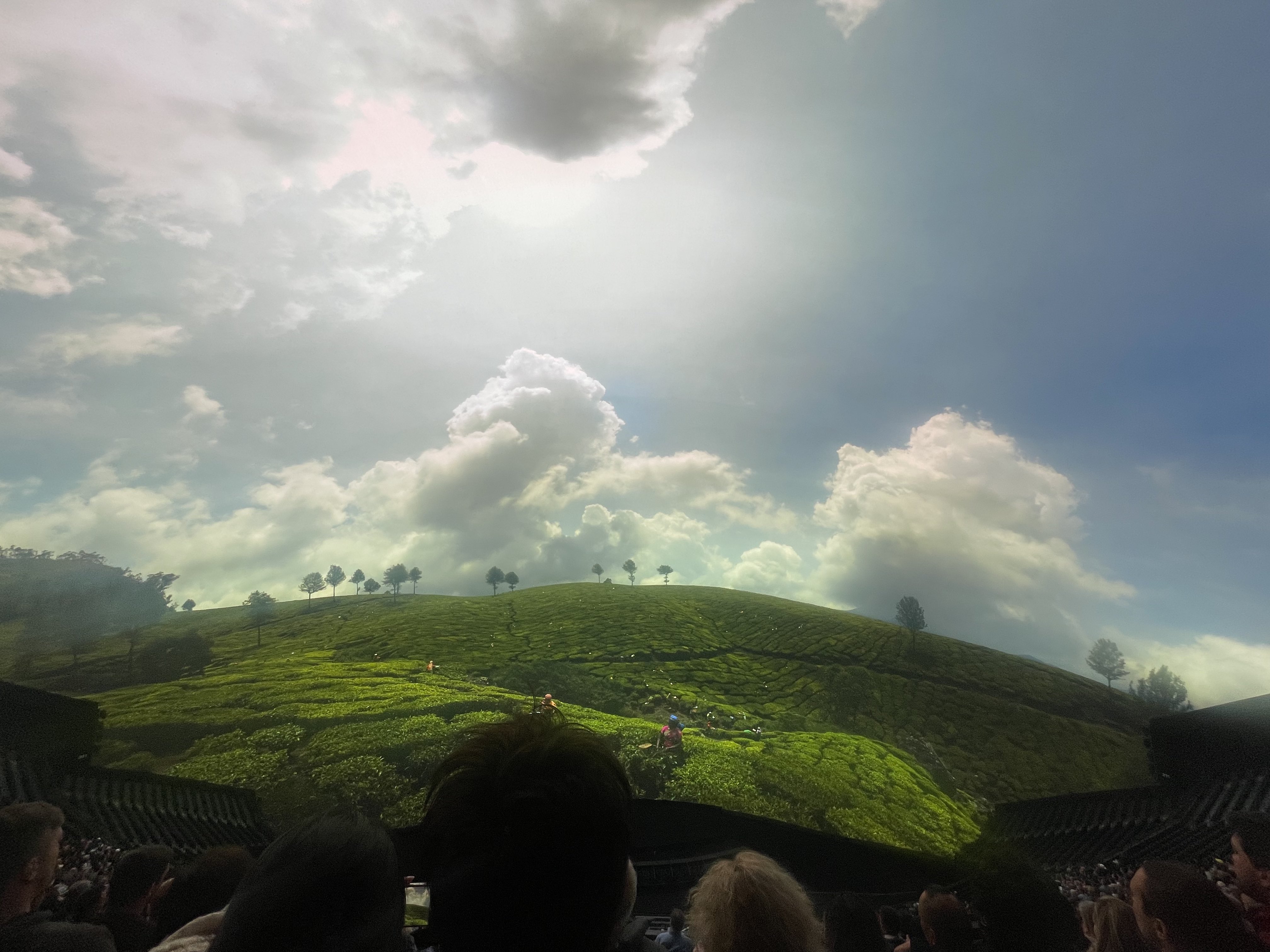

That sense of looming disaster creeps in again. The hotel cafe is playing these covers of hit songs because of licensing — on the walls are these canvas prints: the New York City skyline, the Flatiron Building, the Empire State Building, the Brooklyn Bridge, and one with words: SUNSET BLVD, RODEO DRIVE, OLVERA STREET, MELROSE, SANTA MONICA BOULEVARD, LA CIENEGA, DOHENY DRIVE, PACIFIC COAST HIGHWAY, LOS FELIZ, LA BREA AVE, WESTWOOD BOULEVARD. I walked past New York New York, I walked past the Eiffel Tower, I walked through the Venetian and the Bellagio, the simulacra quickly became exhausting and boring.

From Jhumpa Lahiri's Traduzione (stra)ordinaria / (Extra)ordinary translation — On Gramsci:

The notebook entries are provisional, fragmentary; private jottings that will be elaborated and further articulated. Within the notebooks, certain ideas are elaborated over and over. The letters feel more coherent, contained, structured. If the notebook entries are in some sense forbidding (though utterly fascinating) in that they are diaristic, more interior, the letters, also interior, are a form of narrative that points outward and, indeed, may be read as an unfolding story, as drama. The letters are always crossing the border and responding to outside voices, to an awareness and longing for the other. It is in the letters, and only in the letters, and then only rarely, that he exposes his intense isolation, vulnerability, and desperation. The strange effect of reading the letters is that, in hearing only what Gramsci writes but not what he receives in return, we experience only a single strand of a double thread.

Originale/original, from the Latin origo, meaning origin, roots us to beginnings, to the act of coming into being, to founding myths, to the places in which we begin, to our parents and ancestors, to where narratives emerge and to the sources from which words derive. But an origin also gives rise to a point of departure. The highly original work of Gramsci has spawned translations, not just “literal” translations from one language to another but meaningful heuristic offshoots in the form of scholarly analysis, all of which underscores the fact that translation describes the process of one text that becomes many.

In inventing new names, in declining them, Gramsci is transforming identity, reinforcing his affection for those he loves. The playful (and subversive) act of renaming is one form of overturning, of questioning language and identity in its most essentially linked form. Renaming is a form of translation and also a form of love.

What I read, in the letters, was only one side of a conversation. But what I learned was just how crucial conversation and communication were for Gramsci. As I mentioned, the letters and the notebooks are in conversation with each other. If one is a monologue, the other is an intended dialogue. One is a type of diary or letter to oneself. The other is a correspondence with various individuals. But the letters are also internal conversations, ruminations, and intellectual explorations, conversations as much with himself as with others. What is pointed inward is vast and global, while what is outward is often intensely personal. They must be read together: in many ways, one is the translation of the other.

We can think of translation as a back-and-forth, and we can detect this in very real terms as the letters are sent off and arrive, and packages are received, or not. It is the back-and-forth of language across time and space that sustains him.

In reflecting upon certain words in prison, Gramsci gave us a new vocabulary. Though he did not invent words like hegemony and praxis, he revised our understanding of them, redefined them, and caused them to circulate and to resonate differently. He translates and transforms these terms, with their Ancient Greek roots, by means of reading and reinterpreting them.

In the letter of September 20, 1931, as he lays down his thoughts on Canto X of Dante’s Inferno, Gramsci talks about language that changes, a fact that generates the activity of translation throughout history. It is the very fact of language as something that is always changing, always becoming something else, that instigates, necessitates, and perpetuates the act of translation. This also explains why translation is the underpinning of revolution.

What makes the letters a great work of literature is the complexity of the voice. And though they can be read as a sustained first-person novel, in fact that voice changes from letter to letter depending on whom he writes to and when, shifting from irony to sincerity, from light to dark, from recipes to philosophy, from matter-of-fact concerns to haunting reflections. This fluctuation is especially striking when he writes to different people on the same day. This would be the greatest challenge, for the translator: to give voice, in another language, to each of these individual voices.

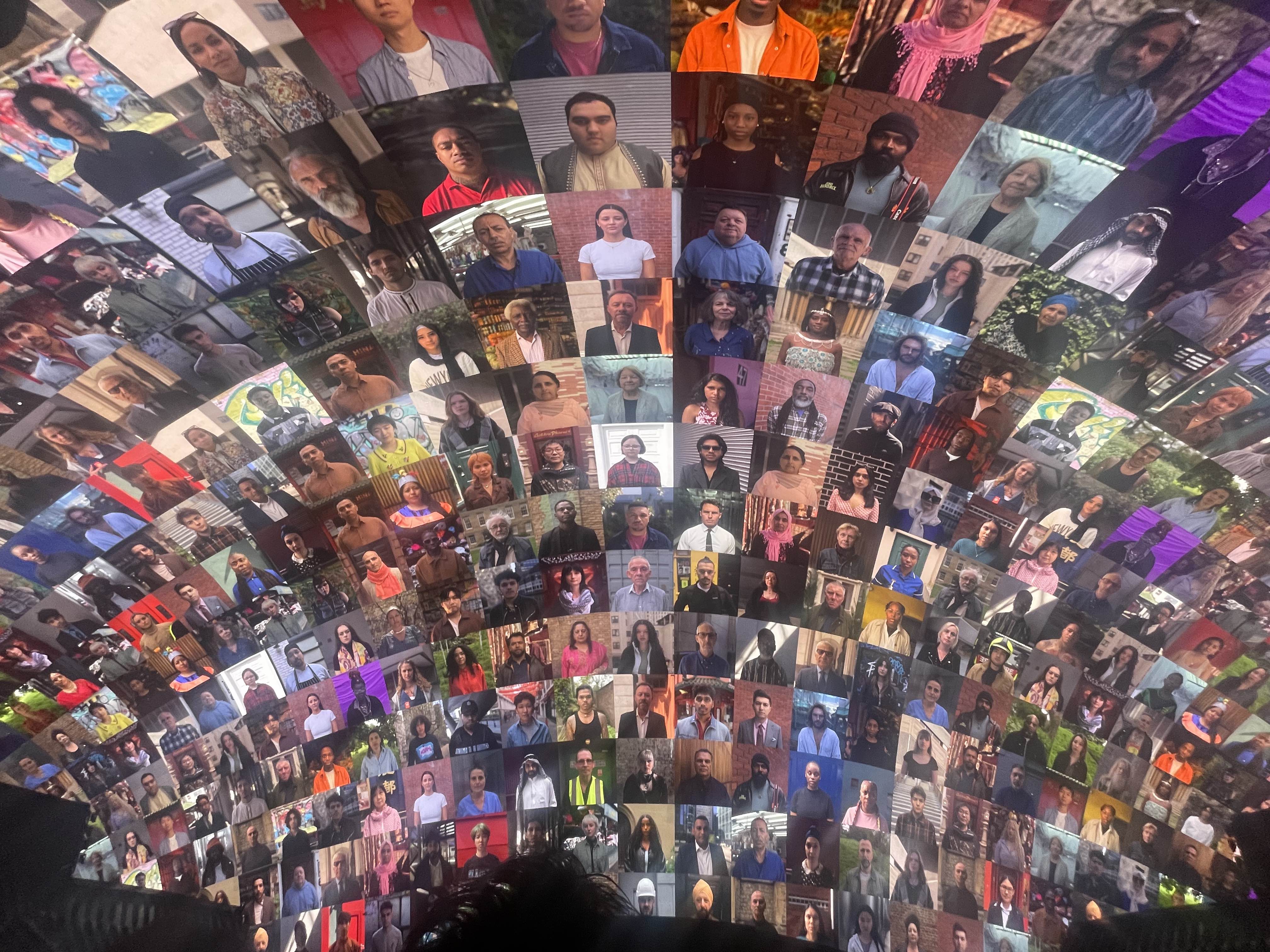

The Greek adjective connected to the concept of cosmopolitan, κοσμοπολίτης/kosmopolitēs, is a compound of κόσμος/kosmos (world) and πολίτης/politēs (citizen): a hybrid word to represent a hybrid attitude toward identity and belonging. It was the Presocratic philosopher Diogenes who coined the compound word, refusing to give a specific answer to the question of where he was from. Cosmopolitanism, then, with its political origins, redefined and resisted notions of nationhood and the state. Fittingly, Gramsci has an ambivalent relationship with this two-sided term. On the one hand, we can point to cosmopolitan aspects of his personal background, his essence, his thinking across languages. On the other hand, he is deeply critical of the role and legacy of the “cosmopolitan” Italian intellectual. On November 17, 1930, he writes to Tania about the “funzione cosmopolita che hanno avuto gli intellettuali italiani fino al settecento / the cosmopolitan role of Italian intellectuals until the eighteenth century.” He continues, “credo che ci sarebbe da fare un libro veramente interessante e che non ancora esiste / I think there’s an interesting book to write about this, one that doesn’t exist yet.”

Peter Ives and Rocco Lacorte remind us of the problematic connotations of cosmopolitanism for Gramsci in regard to translation: “All too often, the concept of translation (not unlike language) is stripped of its political content and used to cast a vaguely positive glow of acceptance, accessibility, and interest in things ‘other.’ For Gramsci, in contrast, translation is always political and related to questions of revolution.”